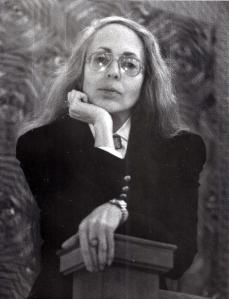

MICHAEL A. VENTRELLA: Today, I am pleased to be interviewing Hugo-nominated author Janet Morris. Janet is probably best known for her Silistra series.  She has contributed short fiction to the shared universe fantasy series “Thieves World” and then created, orchestrated, and edited the fantasy series “Heroes in Hell,” writing stories for the series. Most of her fiction work has been in the fantasy and science fiction genres, although she has also written historical and other novels. Her 1983 book I, THE SUN, a detailed biographical novel about the Hittite King Suppiluliuma I, was praised for its historical accuracy.

She has contributed short fiction to the shared universe fantasy series “Thieves World” and then created, orchestrated, and edited the fantasy series “Heroes in Hell,” writing stories for the series. Most of her fiction work has been in the fantasy and science fiction genres, although she has also written historical and other novels. Her 1983 book I, THE SUN, a detailed biographical novel about the Hittite King Suppiluliuma I, was praised for its historical accuracy.

Janet, let’s start by talking about the Kindle promotion going on right now.

JANET MORRIS: There is an Amazon giveaway (May 15-17) of the author’s cut reissue of BEYOND SANCTUARY as a Kindle book. This is the only time this book will be offered as a free Kindle download.

It the first novel in the “Author’s Cut” group of reissues: each “Author’s Cut” volume is compeltely revised and expanded by the author(s) and contain new material never before available. The other “Author’s Cut” volumes that have been released as ebooks and as trade paperbacks are TEMPUS WITH HIS RIGHT-SIDE COMPANION NIKO (2011) and THE FISH THE FIGHTERS AND THE SONG-GIRL (2012). The next “Author’s Cut” edition will be BEYOND THE VEIL (2013), second of the three “Beyond novels” in the Sacred Band of Stepsons series. We will eventually reissue all the Sacred Band of Stepsons books, and then more of our backlist, in this ‘author’s cut’ program. It’s very satisfying to get all the errors and deficiencies corrected, and have a chance to enhance these perennial sellers.

Most Sacred Band novels will not have giveaways; we chose BEYOND SANCTUARY as a good starting place for those new to the series and, in its enhanced and expanded form, as an attraction for those who loved these books and stories in the 20th century. We are planning to do a few Sacred Band stories as Kindle shorts as time goes by, but nothing specific has been decided.

VENTRELLA: You started your publication history with the Silistra series. How did you make that first sale?

MORRIS: I wrote HIGH COUCH in 1975 and its two follow-ons, THE GOLDEN SWORD and WIND FROM THE ABYSS thereafter for fun: following the story for my husband and our friends. I knew no one in publishing and had no aspirations to break into the business.

One friend said her husband knew an agent and the book (HIGH COUCH) should be published but I would need to provide the manuscript in a clean, double-spaced copy, not single-space with handwritten corrections. I had my dad’s ancient typewriter (non-electric, non-correcting; the “p” key stuck) and was a terrible typist. I found out it would cost $1.00 per page to have the manuscript typed by a professional, which meant a $250.00 investment. So I didn’t do that for over a year; by then my second book was finished. In 1976 my friend sent the typed HIGH COUCH manuscript to an agent, Perry Knowlton, president of Curtis Brown, Ltd.. Perry called me and said I was a natural storyteller and he wanted to represent me and the book, and did I have any other books? I said I did but they weren’t typed up. He said, “Get them typed.”

Perry remained my only agent until his death. By the time I had the other books typed, he had sold HIGH COUCH for five figures to Frederik Pohl and Sydney Weinberg at Bantam and I was able to quit my day job. Then Perry sold THE GOLDEN SWORD and WIND FROM THE ABYSS to them in a package. By then I was writing THE CARNELIAN THRONE. By the time THRONE came out, Bantam had over 4M copies of the first three in print.

They bought THE CARNELIAN THRONE also, and my next series went to auction in two countries simultaneously based on sample chapters: I still don’t like to write outlines.

Silistra got many foreign rights deals, but only the French one is a divergent manuscript: for a sizable additional sum, I provided extra ‘erotic passages.’  ‘Erotic’ in those days was much less explicit than now, but even so, SILISTRA shook a lot of people from complacency: it wasn’t feminist, nor was it conservative; it featured pansexual characters and dealt with philosophical and sociobiological questions about sexuality and abuse of power; the main female character was powerful and had a sword: all these elements were challenging to the fantasy and SF community. And the book didn’t fit a neat category. In what was then a very hidebound and immature market, it blazed tough trails and still today doesn’t fit any simplistic or political model.

‘Erotic’ in those days was much less explicit than now, but even so, SILISTRA shook a lot of people from complacency: it wasn’t feminist, nor was it conservative; it featured pansexual characters and dealt with philosophical and sociobiological questions about sexuality and abuse of power; the main female character was powerful and had a sword: all these elements were challenging to the fantasy and SF community. And the book didn’t fit a neat category. In what was then a very hidebound and immature market, it blazed tough trails and still today doesn’t fit any simplistic or political model.

VENTRELLA: How has the publishing world changed since then?

MORRIS: E-publishing is a big change. Deconstructionism is rampant: the continual division of the novel into smaller and smaller subsets of its constituent elements (such as mystery, thriller, erotic, adventure, romance, horror, etc.) either mirrors or leads the deconstruction of politics and of society. Writing outside established marketing categories is increasingly difficult; the mid-list book, which was an incubator of talent, is all but gone in print publishing.

As an ox-gorer and a windmill-tilter who writes mythic novels with political subtexts and who never has been easy to categorize, I think e-publishing is a good thing. I no longer have to cut a big idea into three volume-sized chunks: I can write the book at the length it needs; I don’t have to fix or endure additional errors from semi-educated production people; I can control my covers and the book’s sell copy. The downside is there is much more free reading material (some worth the price, some not), and a lower educational level among some groups – but there have always been books and writers for every echelon of society.

VENTRELLA: Do you see a future where self-publishing will be accepted?

MORRIS: Sure, eventually. When we decided to return to fiction (after taking 20 years off to create the nonlethal weapons mandate, the nonlethality concept, and other initiatives in the defense policy and planning realms), we wanted to keep our fiction e-rights and at that time my agent (Perry Knowlton’s son, Tim, at Curtis Brown) said it was impossible to make a deal like that with a major house. So we decided to put together a small publishing house that did e-books and trades and make strategic alliances with other small publishing houses who produced quality hardcovers. We did this because the self-publishing road is still stigmatized, and because the production learning curve is steep. Kerlak did our first two hardcovers and gave me what I wanted: sewn binding, linen boards, generous print size, etc.

The stigmatization of self-publishing is primarily from the big chains, who look down on POD but POD was what attracted me to small publishing: no remaindered books; no books going to dumpsites; no torn-off covers returned and no tax liability for unsold stock. When we do reissues, we do “Author’s Cut” editions in which we can correct and expand and enhance each book that we’re releasing with better covers and production values than the twentieth century originals: an approach possible now but not practical even ten years ago.

Machiavelli commented in THE PRINCE as follows: “There is nothing more difficult to carry out nor more uncertain of success nor more dangerous to handle than to initiate a new order of things: for the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in those who would profit by the new; this weak support arising partly from the incredulity of mankind who does not truly believe in anything new until they actually experience it.”  We found this when initiating the nonlethal weapons programmatics: twenty years later, we are where we should have been in five years in nonlethals, and at absurd cost because nothing is adopted until big things take that viewpoint onboard commercially. Similarly, with publishing, as vested interests deal themselves in and competitive entities are created, things will stabilize – hopefully with new players, but with many of the old entities in new guises.

We found this when initiating the nonlethal weapons programmatics: twenty years later, we are where we should have been in five years in nonlethals, and at absurd cost because nothing is adopted until big things take that viewpoint onboard commercially. Similarly, with publishing, as vested interests deal themselves in and competitive entities are created, things will stabilize – hopefully with new players, but with many of the old entities in new guises.

VENTRELLA: Will the rise of smaller publishing houses and e-books mean that these may someday be better accepted? For instance, will SFWA someday accept more of these publishers? Would that be a good thing?

MORRIS: Eventually the writers organizations must accept reality. E-books and small publishing are part of the new reality. SFWA, like all bureaucracies, protests that it protects its membership while it actually protects primarily itself. When SFWA sees that it must change to survive, it will change. Adaptation is always necessary for survival.

VENTRELLA: Now let’s talk about something more fun: Writing! What led you to write fantasy?

MORRIS: My work doesn’t fit many contemporary definitions of fantasy. I really write mythic novels and stories, sometimes in an SF and sometimes in a fantasy context, but there’s nothing ‘sweet’ or ‘pastel’ about my work: my characters face challenges and so do my readers.

When I write something that publishers call ‘fantasy’ I am writing in what I think is the most important tradition of fiction: starting with Homer and up through Shakespeare and Milton, the most important themes to tackle are those of the mythopoeic domain, tales of the body and mind seen through a temperament and a cosmos divorced from current reality so what is said can be more clear. For me, myth is the ‘common’ language of us all – or has been until these days of stories reduced to their lowest mechanical nature. My stories have a historical cognizance, a literary cognizance, and a philosophical/ scientific cognizance.

Bantam once wanted to separate a book of mine into two books: a short ‘wisdom literature’ book and a longer ‘mainstream’ book. I didn’t do that, but in retrospect it was a well-thought impulse on the publisher’s part.

I’ve also written nonfiction; a rigorous historical about Suppiluliumas, a Hittite king; a pseudonymous ‘novel’; other pseudonymous ‘high-tech thrillers’ (or what you will) with strong technology drivers. I make more money when I write under one male name than when I write under one female name or, as reality dictates, as “Janet Morris and Chris Morris.” But I write the book, each time, that forces me to write it, whether fiction or nonfiction. If the book is fiction, I write only when the story and characters demand that I give up my real life because what they will say is more important.

VENTRELLA: How do you create a realistic, believable fantasy world without just looking like every other realistic, believable fantasy world out there?

MORRIS: We say about THE SACRED BAND, our newest mythic novel, that it is “an adventure like no other.” This book had waited since the late 1970s to be written.

My books are remarkably unlike most of what else is available in contemporary fiction, so making the story or milieu ‘unique’ is not an effort for me.  We started ‘The Sacred Band of Stepsons’ series and characters in the ‘shared world’ universe of Thieves’ World®, and so wrote in a milieu populated with other writers: making my work ‘fit’ their construct was a challenge. I have a deep love for the third, second and first millennia BCE, and my ancient characters always are touchstones to historical reality: I don’t “try” to make my fantasy world different from reality: I try to take you into the mythos of humanity. Silistra had a complete language, a glossary, a unique context, a rigorous rationale actually based on sociobiology and genetics, but had sword-wielding women and horses and ancient skirmishers as well as high-tech outsiders trying to understand it. The “Dream Dancer” series, also ‘science-fantasy,’ was set in space habitats primarily. It’s very easy for me to establish a credible world construct and posit behaviors there: I have predicted several major events in the real world over a number of years based on that ability to identify the most likely course of action that a country or individual will take in a given context. Now this skill is beginning to become a field of study called “intuitive decision making” and also “implied learning.” We once called it “speed understanding.” Writers often have this ability, and it allows creators to make their characters and societies credible. The writers who don’t have it can’t make their characters, or worlds, credible enough to please me.

We started ‘The Sacred Band of Stepsons’ series and characters in the ‘shared world’ universe of Thieves’ World®, and so wrote in a milieu populated with other writers: making my work ‘fit’ their construct was a challenge. I have a deep love for the third, second and first millennia BCE, and my ancient characters always are touchstones to historical reality: I don’t “try” to make my fantasy world different from reality: I try to take you into the mythos of humanity. Silistra had a complete language, a glossary, a unique context, a rigorous rationale actually based on sociobiology and genetics, but had sword-wielding women and horses and ancient skirmishers as well as high-tech outsiders trying to understand it. The “Dream Dancer” series, also ‘science-fantasy,’ was set in space habitats primarily. It’s very easy for me to establish a credible world construct and posit behaviors there: I have predicted several major events in the real world over a number of years based on that ability to identify the most likely course of action that a country or individual will take in a given context. Now this skill is beginning to become a field of study called “intuitive decision making” and also “implied learning.” We once called it “speed understanding.” Writers often have this ability, and it allows creators to make their characters and societies credible. The writers who don’t have it can’t make their characters, or worlds, credible enough to please me.

If you want to write something completely unique, you will probably fail or at best write something without redeeming value. The mind works in certain patterns: the mind organizes facts in story form; it is your commonality with that body of human thought that makes a good book, not its estrangement from the common values that humans share.

VENTRELLA: As one of the original THIEVES’ WORLD gang, you’ve had a huge influence on modern fantasy fiction. It’s one of the first (or maybe the first?) shared world anthology. (I copied it completely and stole this idea for my TALES OF FORTANNIS series, by the way.) Where did the idea for this originate?

MORRIS: TW had one volume published when I was asked to come aboard: “Thieves’ World,” which had Joe Haldeman and Andy Offutt and Bob Asprin and others. Bob had the original idea for the “worst town in fantasy, the grittiest, meanest, seediest place possible.” He asked me to write for it at a convention and I said, “How serious are you about gritty?” I had written a very short piece about a woman who killed sorcerers for a living, and I proposed to bring those characters into Thieves’ World, plus an immortalized and very unhappy mercenary who regenerated. Bob said okay, I could bring the characters and take them out again afterward.

I started the story “Vashanka’s Minion,” that introduced Tempus (a/k/a the Riddler, Favorite of the Storm God, the Obscure, the Black). He has a metaphysical link to Herakleitos of Ephesus, and lives as a warrior in a Herakleitan/Hittite cosmos that I overlayed on what Bob and Andy already had done. But when Tempus got down to the dock and Askelon of Meridian got off the boat, Tempus said, “You, get out of my story. There’s not room enough here for both of us.” So Askelon didn’t arrive in Thieves’ World until “Wizard Weather,” although Cime, Tempus’ sister-in-arms, did show up. Tempus forms the Sacred Band of Stepsons in Thieves’ World #2, meets the patron shade of the Sacred Band in #3, and puts the Band together.

Then the TW books start to succeed and people get cranky. I called Bob and asked for a letter because I wanted to take my characters out of the shared town and do a group of novels with them, since Bob was complaining my characters were “too big.” So we agreed on that plan. These tensions made the stories more fun: people came and went; I took my characters into my own constructs such as Wizardwall and into the real ancient-world settlements of Nisibis and Mygdonia. Everyone contributed something useful to TW, and its fabric is still very rich.

I got Lynn Abbey’s permission, after Bob died, to bring the Sacred Band back to Sanctuary for a big novel to tie up loose ends that was set ten years after the Stepsons left town in TW #11 and well before Lynn’s own novel, since that milieu wouldn’t work for me. This project became THE SACRED BAND.  As agreed with Lynn, THE SACRED BAND was followed by a novella, “the Fish the Fighters and the Song-girl” (the title story from the second “Sacred Band Tales” anthology), which takes the Stepsons back out of Sanctuary again and sweeps up all my TW stories not previously collected. So now, between “Tempus with his right-side companion Niko” and “the Fish the Fighters and the Song-girl” all our ten TW Sacred Band stories are assembled in two volumes, along with other Stepsons tales not available elsewhere.

As agreed with Lynn, THE SACRED BAND was followed by a novella, “the Fish the Fighters and the Song-girl” (the title story from the second “Sacred Band Tales” anthology), which takes the Stepsons back out of Sanctuary again and sweeps up all my TW stories not previously collected. So now, between “Tempus with his right-side companion Niko” and “the Fish the Fighters and the Song-girl” all our ten TW Sacred Band stories are assembled in two volumes, along with other Stepsons tales not available elsewhere.

As for fun quotient, I get more joy from the Sacred Band of Stepsons than from any other characters. And the SBS character list is expanding….

VENTRELLA: Another great series you’ve run is the HEROES IN HELL series (which now apparently includes LAWYERS IN HELL, which could be the name of my autobiography). What future themes can we expect to see?

MORRIS: If I’d known you, I’d have invited you to contribute to LAWYERS. In the 21st century Heroes in Hell books, next up is “Rogues,” to be followed by “Dreamers” (or “Visionaries,” I haven’t finalized the title), then “Poets,” then “Pirates” (or “Swashbucklers”). “Doctors” is a distinct possibility. There are many stories left to tell in hell, especially now that we have met hell’s landlords and heaven has sent down auditors to make sure hell is sufficiently hellish.

VENTRELLA: How do you work with the authors to make sure there is consistency in the world setting for these collections?

MORRIS: Each hell book takes a year to write and assemble, and the writers must coordinate more completely than was possible before the internet: we have a “secret” working group on Facebook where the writers interact and arcs and meta-arcs are chosen and polished. They choose characters. Our “Muse of Hell,” Sarah Hulcy, has put up 130 orientation docs, so there’s plenty of available information. When they choose the characters, we check to see if those characters have been used previously, and if the characters are available and meet our criteria, they can “claim” those characters for the time they write for the series. If they leave, they can’t take the characters: characters come back to me and stay in hell to be recycled.

Then they work on a short “two or three sentence” synopsis. I must accept the synopsis and the characters before they start to write. They can use legendary, historical, or mythical characters. They can’t use characters from modern fiction (post 1900) and they can’t use recently dead or living people. Then writers are allowed to post in-progress snippets which the group can read, and comment upon – or not. Chris and I write “guide stories” (two or three), setting up the current long arcs and the general tone of the volume at its beginning and end. Between these “bookends,” the other writers must set their stories.

When the stories are generally selected, I edit for continuity and tone, and Sarah Hulcy follows me with a copy-edit. Chris Morris is the final editorial reader, and with the three of us working on the stories for continuity and cohesion, we get a strong result and a better book than we could have produced before the internet.

VENTRELLA: I assume your anthologies are primarily invitation-only (correct me if I am wrong).  How do you deal with stories that don’t meet your standard or are rejected for other reasons?

How do you deal with stories that don’t meet your standard or are rejected for other reasons?

MORRIS: We are invitation-only. The milieu of our hell belongs to Chris and me. The authors know that from the outset. We usually won’t let them write a story we don’t think will work: by the time we’ve approved characters and synopsis, we know what the story will be and how we’ll use it. If someone simply fails to write a useful story, they probably haven’t met our guidelines. Our hell universe is easily recognizable. Each writer has left a clear trail of participation. If they want to rewrite a story we won’t accept and take out the arguably HIH context and characters, of course they can try.

VENTRELLA: Let’s discuss your novels. Which is your favorite?

MORRIS: In fantasy: THE SACRED BAND (Janet Morris and Chris Morris; Paradise, 2010; Kerlak, 2011), the mythic novel of the Sacred Band of Stepsons uniting with the Sacred Band of Thebes and returning to Sanctuary. In historical: I, THE SUN (Janet Morris, Dell, 1987).

VENTRELLA: Who is your favorite character?

MORRIS: Tempus and then Niko and the Sacred Band of Stepsons fighters.

VENTRELLA: What would you ask that character if you could meet him or her?

MORRIS: Tempus lives in my skull. I meet him on a regular basis and I’m happy to have a character so available. He’s been there since 1979. I went to the White House and he said, “Kinda small, isn’t it?” I would ask him, in all seriousness, whether he truly believes that “character is destiny,” a line he shares with Herakleitos.

VENTRELLA: And what do you think he or she would answer?

MORRIS: “The sun is new every day.” We call him the Riddler, remember.

VENTRELLA: Do you prefer writing fantasy or science fiction?

MORRIS: Fantasy, because very little in SF can transcend the gimmickry of a technical conceit, yet without that conceit at its heart a book isn’t truly science fiction. Furthermore, so little emerging thought and technology is employed by sf writers today that the genre is lagging far behind reality both in the cosmology area and the technology area: sf is no longer a place to experiment, but is now very derivative.

VENTRELLA: Do you find novels easier to write than short stories?

MORRIS: A novel is a major commitment, and must move smoothly along its trajectory. A “short story,” if it’s more than three thousand words, actually lets you focus more deeply on a circumscribed area or event.  I think short stories and novels are different; each form is unique and equally demanding. I prefer novels but short stories are good exercises in discipline.

I think short stories and novels are different; each form is unique and equally demanding. I prefer novels but short stories are good exercises in discipline.

VENTRELLA: Do you tend to outline heavily or just jump right in? What is your writing style?

MORRIS: I don’t “outline” in the way that you mean. I get characters, and their background; I immerse my intelligence in a milieu that’s fully realized: a place with weather and politics and problems and a special nature. I use square post-it notes to write down certain things that must happen during a sitting: a line of dialogue, a particular event, where I need to be when the section is done; a section or chapter or story title. I know where I want the story or chapter or novel to end; I know where I want to start each section: how I get there is the fun for me.

Often times the question for me is which viewpoint character will have the best take on a particular set of events. When I have (twice) sold a project based on outline, it took all the fun out of it.

VENTRELLA: When creating believable characters, what techniques do you use?

MORRIS: I wait. I lie on the bed or go for a drive with paper in my pocket and wait for the characters to start to interact with me, or to tell their story to me. I need to “see something moving” and other writers who write this way all agree – if there’s something moving in your mind’s eye, there’s a character there.

Abarsis was a good example: I knew I wanted to do “A Man and His God” in which at the end the Slaughter Priest would die in Tempus’ arms. I got a character called Abarsis. I thought he and the Slaughter Priest would be two different people but the character wanted to be “Abarsis, the Slaughter Priest.” This was a very big, very strong character and I argued that if Abarsis was the Slaughter Priest then he would die. He said that was fine. Susan Allison of Ace called me up after she read it and confessed that the story made her cry. And Abarsis came back as patron shade of the Sacred Band: the character knew more than I what to do and how, in order to be memorable. Sometimes with good characters you must let go and let them forge ahead. This requires belief in your Muse.

VENTRELLA: You’ve collaborated with other prominent authors, at least one of whom lives with you, which makes it easier. How have these worked? (For instance, do you share writing equally? Does one author do the basic work and the other expand from that outline?)

MORRIS: With whatever writer, we talk about the story line, points of interest, what needs to be accomplished.  If it’s Chris, he may come up with a title or a concept. I usually do draft or if I write with others, I’ll often write first: I like beginnings. With some writers, I send sections and they pick up the action; with others, I’ll do a draft and then they will add to it after I’ve done all I want to do, from beginning to end.

If it’s Chris, he may come up with a title or a concept. I usually do draft or if I write with others, I’ll often write first: I like beginnings. With some writers, I send sections and they pick up the action; with others, I’ll do a draft and then they will add to it after I’ve done all I want to do, from beginning to end.

Everyone has a special genius, and working with each person is different. If the other writer starts, that’s a different process for me: I work on the story they’ve sent in Track Changes, do what I want to the entire manuscript. Then they accept or reject or we go back and forth. I worked a number of projects with a writer who was outline-driven and I could never figure out what those notations were supposed to evoke, so I’d call to discuss it. The outline made the other writer feel better. I can do a series of chapter titles and use those as an outline, but beyond that, outlines don’t help me. I often work with other writers who don’t like to outline either, or outline in the most cursory way.

VENTRELLA: Writers who are trying to make a name get hammered with lots of advice: The importance of a strong opening, admonitions about “writing what you know,” warnings to have “tension on every page” – what advice do you think is commonly given that really should be ignored?

MORRIS: All advice should be ignored. Every real writer is different. Every story has a nature, an organic way it wants to unfold. Tell a story that sweeps you up, that you want to hear, that keeps YOU on the edge of your seat. Some stories start best with dialogue, others with narrative: writing is catching the wave of creativity. The wave must be there for you to catch.

Writers learn from reading other writers whom they can admire, and writers whom they detest. Before Silistra, I bought a paperback by a famous writer and when I was done I threw it in the wastebasket, said “I can do better than that,” and did. When I read, I try to read writers who can teach me something, who are better at some things than I am. But print-through is always an issue: often when I am writing fiction I read only nonfiction, and vice versa.

The only person who should ask you to make changes in your book is some editor who has paid a lot of money for it. Even then, changes are risky: the story unfolds on the first pass the way the universe unfolded in the first moments of creation: in the way that it must.

VENTRELLA: What is the biggest mistake you see starting writers make?

MORRIS: Writers who have no characters and force a story bore me. Writers who are good at one thing – such as dialogue – may do that one thing too much: talking heads don’t work except very occasionally, when they can work very well. Knowing when to do something is part of the art of writing. Sometimes I act as an acquisitions editor. If you want to sell to me, you’ll tell me who, where, what, and why, and then finally how – all on the first page, hopefully in the first couple paragraphs: where I am, what it’s like, who cares about what’s happening. I want to fall through the words into a different place. But most of all, you must make me care almost immediately.

VENTRELLA: With a time machine and a universal translator, who would you invite to your ultimate dinner party?

MORRIS: Homer, Hesiod, Tiye, Virgil, Marcus Aurelius, Herakleitos, Einstein, DaVinci, Xenophon, Kikkuli, Thales, Plato, Odysseus (assuming he was Homer’s grandfather), Epaminondas, T.E. Lawrence, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Byron, Mary Shelley, Evelyn Waugh, Emil Zola, Dwight Eisenhower, Sun Tzu, Aspasia, Aristotle, Marguerite Yourcenar, Henry James, Suppiluliumas, Anksepaaten, Herodotus, Sappho, Emily Dickinson, Richmond Lattimore, Solomon, the Biblical “J.” And I’d really like to have Roger Penrose as toastmaster, but he’s still alive.

Filed under: writing | Tagged: agents, e-book, fantasy world creation, Heroes in Hell, Janet Morris, outlines, publishing house, science fiction, self-publishing, short stories, Silistra, Tempus, Thieve's World, writing advice | 1 Comment »

Her science-fantasy series “The Children of the Desert” is set in a world still struggling through a number of basic moral and developmental issues. Her webpage is here.

Her science-fantasy series “The Children of the Desert” is set in a world still struggling through a number of basic moral and developmental issues. Her webpage is here. I earned straight A’s in English class — when I turned in my homework, of course. That was always a problem. Homework is so boring…

I earned straight A’s in English class — when I turned in my homework, of course. That was always a problem. Homework is so boring…

In one of my stories (“Silver and Iron”, Sha’Daa: Pawns), an evil fae makes plans to sacrifice her lover in order to summon demons, then goes to the grocery store and deals with traffic jams. “Believable” roots in common experiences, in keeping a foot in what we see as real life. Meals are a really easy way of hitting that shared note, because everyone has to eat. Basic weather changes also give the character and the reader to meet on common ground.

In one of my stories (“Silver and Iron”, Sha’Daa: Pawns), an evil fae makes plans to sacrifice her lover in order to summon demons, then goes to the grocery store and deals with traffic jams. “Believable” roots in common experiences, in keeping a foot in what we see as real life. Meals are a really easy way of hitting that shared note, because everyone has to eat. Basic weather changes also give the character and the reader to meet on common ground.