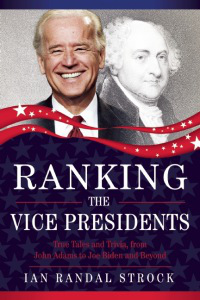

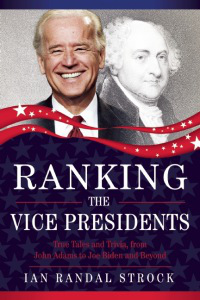

MICHAEL A. VENTRELLA: Today I’m pleased to be interviewing Ian Randal Strock, a good friend who has helped me out at many conventions with the Eye of Argon reading. Ian is the owner and publisher of Gray Rabbit Publications, LLC, and its sf imprint, Fantastic Books. He thinks of himself as a science fiction author, even though 98% of his published words have been non-fiction.  He’s the winner of two AnLab Awards from his writings in Analog, and the author of THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS (Random House, 2008), RANKING THE FIRST LADIES (Carrel Books, 2016), and RANKING THE VICE PRESIDENTS (Carrel Books, 2016). His name is unique on the internet, but having such a varied resume means that many of those pages look like they’re talking about different people, so he recently launched his own eponymous web site, just to draw them together to some degree.

He’s the winner of two AnLab Awards from his writings in Analog, and the author of THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS (Random House, 2008), RANKING THE FIRST LADIES (Carrel Books, 2016), and RANKING THE VICE PRESIDENTS (Carrel Books, 2016). His name is unique on the internet, but having such a varied resume means that many of those pages look like they’re talking about different people, so he recently launched his own eponymous web site, just to draw them together to some degree.

Ian, you have a political science background as I do. Tell me about that and explain how you ended up where you are now.

IAN RANDAL STROCK: I went to college thinking I was going to be a doctor, but half way through, I realized that wasn’t my proper career path. I wandered into the student-owned newspaper, worked my way up the editorial staff, and chose a major in something that had always fascinated me. Unfortunately, there’s just about no place you can walk into and say “Give me a job; I’m a political scientist.” But you can get a job saying “I worked the equivalent of a full-time job on the student newspaper at Boston University, working my way up to Deputy Editorial Page Editor and Assistant Book Review Editor.”

VENTRELLA: What did your years as an editorial assistant teach you?

STROCK: That the world is usually not what you imagine? That I’m immune to hero worship? That even though publication may be ephemeral, there are facets that last a long time? That technological changes can be overwhelming when you look at them in retrospect? That sometimes it pays to play it a little more cautiously? That’s just a few, but perhaps they deserve some fleshing out.

That the world is not what you imagine: After I graduated from college and moved to New York, I looked for a job in publishing. After taking a job that was a mistake, I was looking through the classified ads in the New York Times, and saw a three-line ad: “Wanted: Editorial Assistant for science fiction magazine. 380 Lexington Avenue, NY NY 10017” (I still remember it, though they’ve moved several times since then). I said to myself “I know that address. I’ve been sending them stories. That’s either Analog or Asimov’s.” I sent them my resume with a cover letter that basically said “Gimme the job! Gimme the job! Gimme the job!” I got called in for an interview, and was thrilled to learn that the job was for both Analog and Asimov’s. I knocked on the door, expecting a large reception room and spacious offices beyond, so when I opened the door, I was… surprised. Inside was a room about ten by twenty feet, crammed with five desks, four floor-to-ceiling book cases, and half a dozen file cabinets. This one room was the entire editorial space for the two largest US science fiction magazines. The intern wasn’t allowed to come in on Tuesdays, because that was the day the editors came in (the rest of the week, they worked from home), and there wasn’t a place for him to sit.

That I’m immune to hero worship: My second day at the magazines was a Tuesday. On Tuesdays, the editors came in. And on Tuesdays, Isaac Asimov visited the office. His name was on the magazine, but his only responsibility to it was to write the monthly editorial and to answer the letters. But every Tuesday, he’d come in to the office, talk with the editors, ask if there was anything he needed to know, and socialize. So on my second day at work, in the middle of January (it was cold), I heard this harsh Brooklyn voice coming closer to our door, singing loudly and cheerfully. In walked this nebbish bundled up in a heavy coat with a thick hat wearing big muttonchop sideburns and a big smile. Isaac Asimov. One of those names I’d known since I’d discovered science fiction. He was here! After he’d unwrapped himself, Sheila Williams (one of my bosses, she was the Managing Editor of Asimov’s) introduced us. Isaac looked up at me (he was about 5’9”, I’m 6’2”) and said “you’re not a cute little girl” (my two predecessors in the job had apparently been five-foot-nothing and really cute). I said “you’re not a ten-foot-tall god” (not sure where I found the chutzpah to say that to Isaac Asimov).  He said “I’m not going to make up a limerick for you.” That began our friendship that lasted for the last three years of his life. Two or three months later, Sheila told me one of our authors would be visiting, and I got excited. “I’m going to meet my first author!” I said. And she said “what about Isaac?”

He said “I’m not going to make up a limerick for you.” That began our friendship that lasted for the last three years of his life. Two or three months later, Sheila told me one of our authors would be visiting, and I got excited. “I’m going to meet my first author!” I said. And she said “what about Isaac?”

That even though publication may be ephemeral, there are facets that last a long time: Those crowded book shelves in that tiny little office contained every issue of Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine and of Analog Science Fiction and Fact. Not a week went by that we didn’t get a letter from someone offering to sell us back issues of the magazines, either accumulated or inherited. We had a list of dealers we’d send back to them, but we knew there was almost no call for old magazines. On the other hand, two or three years later, I was involved in a writers’ group for which we were going to share stories of the past that inspired us, and I spent several days trying to find one particular story I’d read in high school. Eventually, having had no luck, I described it to Stanley Schmidt (the editor of Analog). Stan said, “Oh, yes, we published it: ‘Diabologic’ by Eric Frank Russell.” I checked our archives, and pulled the March 1955 issue off those shelves to find the story I’d been looking for.

That technological changes can be overwhelming when you look at them in retrospect: When I walked in the door to interview for that job at Analog and Asimov’s, I was not the least bit surprised to see a typewriter on every desk. By the time I left those magazines six years later, my desk (which had in the interim moved into different offices three or four times) was the only one that had a typewriter on it. I also had a computer on my desk, as did everyone else. And now I think back on how little that poor computer could actually do, with its monochrome monitor and dial-up modem.

That sometimes it pays to play it a little more cautiously: When I walked in for that interview, Sheila and Tina Lee (the Managing Editor at Analog, my other direct boss) asked if I’d be willing to commit to staying in the job for at least a year, because each of my predecessors had left within six months, and they wanted someone who’d stay a little while after being trained in the job. I said of course. They also asked what my career goals were. I said “I’d like one of your jobs, but I really want either Stan or Gardner’s job (Gardner Dozois was the Editor of Asimov’s).” I wound up staying six years, and left because, to my mind, my bosses weren’t getting any older, they weren’t making any moves toward retiring, and when the entire “up” in the company is four people, there’s not a lot of room for advancement. The opportunity came along to start my own magazine (Artemis, which I published until 2003), so I left. I’ve since been through a series of jobs. But if I’d passed on the chance to start Artemis, and instead stuck around, Tina left two years later, and I would have been the Managing Editor of Analog. Then I would have been in the perfect position to move up and become the Editor of Analog when Stan retired in 2012.

VENTRELLA: How did you decide to establish Fantastic Books?

STROCK: I’d published a magazine for several years (Artemis), and been involved in several other start-up businesses, so the entrepreneurial nature of starting a publishing house wasn’t alien to me. A friend of mine was publishing lots of public domain books, and making some money at it, when he decided to start up a science fiction line. He hired me as an acquiring editor, but soon he decided to spin off the line, and I bought it from him. The original concept was a reprint house, bringing back into print authors’ out-of-print back lists (to go along with new books they’re writing and publishing). Soon, however, I decided to take on original titles as well. Now, the company is about half reprints and half original titles. Without consciously planning it, we seem to publish an inordinate number of collections of short fiction (in part because the larger publishing houses are less likely to pick those up). And Fantastic Books is just half the company; the other imprint, Gray Rabbit Publications (which is also the corporate name) is a catch-all for anything else I think will sell: literary fiction, mystery, erotica, history, we have a line of Presidential speeches.…

VENTRELLA: What are you proudest of? New releases or the re-releases of classics?

STROCK: I’m very proud to be one of Michael Moorcock’s publishers, and James Gunn’s, Shariann Lewitt’s, Allen Steele’s, and so on. But the original titles tend to outsell the reprints. Having those big names (and some smaller-name midlist authors) gave the company a jump start when we started publishing original titles by newer authors, and earned us a bit more attention from reviewers (which, in answer to one of your later questions, is one reason to go with a publishing house rather than self-publishing).

James Gunn reminds me of amusing story. We’ve got several of his books available, and I’d been showing them at conventions for probably two years when someone excitedly pointed to them and asked “Are these by the James Gunn?” I said of course, who else? This happened at the next few conventions, until someone pointed out to me that there’s a movie writer/director named James Gunn. Several of my James Gunn’s books were published before that other James Gunn was even born.

Allen Steele is one of our hybrid authors: he is still published by a major New York house, but he’s a long-time friend, and when we started the company, he offered us a few old reprints (including one massive collection which was out of print). We published his collection TALES OF TIME AND SPACE last year. Tor published his latest novel, ARKWRIGHT, earlier this year. I would have published that novel in an instant, but Tor was able to offer him more money and better distribution, so I’m just happy to have some of his new work.

We also had a few reprint titles from Tanith Lee, but a few years ago, she got an offer (with significant money) for the books, and asked for the rights back.  As a small publisher, one of the things I offer authors is a much more personal relationship, so when she asked, I of course said yes. As thanks, she offered me a new collection, and I jumped at the chance. DANCING THROUGH THE FIRE was published on what would have been her 68th birthday last year, and was a Locus Award finalist for Best Collection.

As a small publisher, one of the things I offer authors is a much more personal relationship, so when she asked, I of course said yes. As thanks, she offered me a new collection, and I jumped at the chance. DANCING THROUGH THE FIRE was published on what would have been her 68th birthday last year, and was a Locus Award finalist for Best Collection.

VENTRELLA: What future plans do you have for it?

STROCK: Without planning it, I’m a serial entrepreneur. Gray Rabbit Publications / Fantastic Books is the fifth start-up business I’ve been involved with. But it appears to be the first for which the business plan does not include the line “and then a miracle occurs.” My future plans are to keep running this company and grow it into something that can support me in the manner to which I would like to become accustomed. It’s still at the stage that, like a baby, it will take all the time and effort I can give it, but I can see a day hopefully in the not-too-distant future that it grows to where I want it to be.

VENTRELLA: I have to ask this question because I know some of my readers want to know: Do you take unsolicited manuscripts?

STROCK: No. Emphatically, no. I’ve read piles of unsolicited submissions for several magazines (Asimov’s, Analog, Artemis, Absolute Magnitude) and even for a book publisher (Baen). Fantastic Books is still so small that it makes no financial sense to spend that much time reading unsolicited manuscripts (in fact, I’ve got ten books stacked up on my desk right now for consideration, and those incredibly patient authors haven’t started threatening me yet).

VENTRELLA: What are the things that make you throw a story aside? What frustrates you the most?

STROCK: The one thing that frustrates me the most comes from working with authors who aren’t quite publishable yet. They frequently (painfully frequently) have characters do things because the author needs them to do those things, rather than because the characters would do such things themselves. When you’re writing a story, you’ve created a world, and all the characters in it are your toys to play with as you see fit, to move around to do what you want to do, like a chess board. But just like that chess board, it’s no fun when you move the pieces about randomly: the moves have to follow the rules of the game to make it most exciting. And when you’re creating characters, they have to be believable characters within the world you’ve created.

One scene I remember specifically from a book I edited involved the main character on a ladder. We meet the love interest as he rushes in, cushioning the main character as she falls from the ladder. They have a moment, a brief conversation over the dangers of climbing on ladders, and then the love interest walks out, end of scene. The problem, of course, is that we never learn why the love interest was in the scene in the first place. The author had him there to catch and meet the main character, but in order to make the story believable, the love interest as a person must have had a reason to be there.

VENTRELLA: You’ve written many short stories, but when you finally decided to do a book, you wrote THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS. What inspired you to do that?

STROCK: I’d always been interested in the Presidents, from the time my mother hung a poster in our house with the Presidents’ pictures, names, and dates of office. Soon after I’d memorized that, my earliest political memory is learning that Richard Nixon was going to resign, and asking my parents if that meant Kissinger would be President (since his was the only other political name I knew). They explained about the Vice Presidency, and I was off and running. My brain likes to categorize and rank things, so it wasn’t much of a leap to try ranking the Presidents, seeking out shared characteristics (and wondering if I could acquire those characteristics myself to become President). But it was just a hobby until 2006, when I realized I could turn it into a book. As a writer, most of my output has been short-short stories (I may still have the record for the greatest number of Probability Zero stories in Analog), and I realized I could write my book as a bunch of individual, short-short chapters (because writing a book-length work was daunting). I set out to arrange all the data I had, find the gaps and write new chapters to fill those, and, within six months, I’d written a book.

Then came the problem of what to do with it. I’ve been a science fiction professional long enough that I know all the agents, but none of them had a clue about selling this non-fiction book. Walking around the Brooklyn Book Festival in 2007, I overheard a fellow at a table say to the exhibitor “I’m an agent…” I waited for him to finish his conversation and turn away, then approached him about my book. He wasn’t very encouraging, but offered to look at my proposal, which I promptly sent him. Again, he wasn’t terribly encouraging, but said he was willing to look at the whole book. Receiving that, he said he thought it would be very hard to sell, but he’d be willing to give it a try. And within three weeks, he’d sold it to Villard, which rushed it into print in October 2008.

VENTRELLA: And now, as a follow up, there’s RANKING THE FIRST LADIES. What kind of ranking? How did you make that determination?

STROCK: As with the Presidents, by characteristics that are both measurable and rankable. Important things, like height, longevity, fertility, education…

On the Presidents book, THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS was, in my mind, just a place-holder for a title. But the publisher kept it, and then added the subtitle: “From Most to Least, Elected to Rejected, Worst to Cursed—Fascinating Facts About Our Chief Executives.” In all those 21 words of title and subtitle, far and away, people looking at the book focus on one word almost to the exclusion of the others: “worst.” Without picking up the book, the one question everyone asks is “Who was the worst President?” But I’ve learned that what they mean is “You agree with me when I say XXX is the worst President, don’t you?” 90% of those people go on to tell me that to them, the worst President is either Barack Obama or George W. Bush. It’s really frustrating, because my goal was never to foist my view, my choices on the readers. I really was looking for the characteristics of the Presidents, trying to figure out if I could predict who the next President would be (and for the last two elections, it turns out that the “average President” I created in the book really does predict the winner).

I really was looking for the characteristics of the Presidents, trying to figure out if I could predict who the next President would be (and for the last two elections, it turns out that the “average President” I created in the book really does predict the winner).

VENTRELLA: Was it difficult comparing the First Ladies, given how the role of women has changed so much since Martha Washington?

STROCK: Well, the most recent ones tend to be better educated and have fewer children (on average), but beyond that…

VENTRELLA: Since we will probably have a First Gentleman soon, will that make your book obsolete? Will you have to rename it?

STROCK: The book is a comparison of the Presidential spouses to this point. The fact that all of them have been female is almost incidental. Similarly, the fact that all the Presidents have thus far been male doesn’t seem to be a big point. For instance, in the election of 2008, the candidate closer to the Average President was much closer, and he won. Other than his skin color, Barack Obama looks almost exactly like his 42 predecessors. The only top-five list that changed in that book due to his election was The Five Youngest Presidents (Obama is the fifth youngest to hold office, edging out Grover Cleveland by 182 days.

VENTRELLA: If we call a male President “Mr. President” then why don’t we call a female President “Ms. President”?

STROCK: Actually, we call the male President “Mister President.” “Mr.” is a written abbreviation, but not a spoken abbreviation. “Ms.” on the other hand, has no verbal extension beyond that written abbreviation. I’m guessing that when we have a female President, we’ll probably call her Madam President (because we call female foreign leaders Madame Prime Minster).

VENTRELLA: Let’s talk about writing. How much of writing is innate? In other words, do you believe there are just some people who are born storytellers but simply need to learn technique? Or can anyone become a good writer?

STROCK: I supposed it depends what you want to write. A big thing in writing in these days of easy self-publishing is journaling. Apparently a lot of people feel very satisfied writing down their life stories and having them produced in book form, so in that regard, I guess anyone can be a writer. But in terms of writing something that other people will want to spend money to read, I think that’s a somewhat more rare ability. It may be teachable/learnable, but as with any skill, it requires a lot of effort.

VENTRELLA: Do you think it is important to start by trying to sell short stories or should a beginning author jump right in with a novel?

STROCK: I don’t know about important, but it always made sense to me. Some pundits have said that we have to write through a million words of garbage before we get to the good stuff. Others have said that you have to practice your craft. My thinking is just that the first few things you write probably aren’t going to be very good, you’ll have to keep practicing to learn your craft. If those first few things are short stories, they’ll take a few days or weeks to write. But if those first few things are novels, they’ll take a lot longer to write.

Then again, I’ve had this conversation several times with novelists: I’ll ask how they can possibly write 100,000 words. I sit down to write a story, I get to the end, and it’s 900 words. They’ll respond that they’ve tried to write short stories, and before they’ve finished clearing their throats, the stories are at 30,000 words. So maybe different writers have different innate lengths, and to do the other takes training and effort.

VENTRELLA: What’s your opinion on self-publishing?

STROCK: When I got into professional publishing, and started attending science fiction conventions, the occasional self-published author in a dealers’ room was usually avoided. People would look askance at an author sitting behind a table of books he himself had written and published. But now that I run a publishing house, when I’m at conventions with the books I’ve published, most people walking up to the table are surprised that I didn’t write them. So apparently, self-publishing is much more accepted by the general readership (and since they’re the ones buying the books, it’s their opinion that matters).

But whether you’re self-publishing or going the traditional or small press route, you want your book to look as professional as possible, be as good as possible. A publisher will spend time and money editing, designing, producing, publicizing, distributing your book. Doing it yourself means a lot of your writing time has to be spent on non-writing things. If you’re going to do those things, do them well. A self-published author recently showed me her book, and when I opened it up, the interior was double spaced and ragged right. All I could say to this excited young woman was “very nice, I wish you success with it.” But what I was thinking was “Have you never opened a book before? Do you not see how your book differs, physically, from every professionally published book?”

I own a small publishing company, and I’m also an author. My books have been published by imprints of Random House and Skyhorse. That’s not because I couldn’t do it myself, but as an author, I know the publisher can do things for my books that I can’t. Also, a publisher will pay me an advance that I don’t feel right taking from my own publishing company. They give me greater publicity and distribution. And my marketing efforts—which I would be doing regardless of who published the book—are enhanced by those of the publisher. But in the end, I guess I’m uncomfortable with the thought of self-publishing my own books. Now that other publishers have picked them up—showing that another publisher values them enough to put the time and money into publishing them—if they go out of print, I’ll be much more comfortable bringing them back into print through my own publishing company. And I have actually self-published a few small volumes, which go along with my usual speech topics, to have something to sell at those lectures.

VENTRELLA: What’s the best advice you would give to a starting writer that they probably haven’t already heard?

STROCK: “Don’t do it. There are many less frustrating ways to live your life, so if you can possibly not write, then by all means, don’t. The world needs far more readers than writers.”

That’s the same piece of advice I give every person who asks how to become a writer. I figure if I can save a few of them from being writers, I’ve made those people happier. Of course, most of the people asking that question laugh off my answer, and then tell me they have to be writers (I don’t know how many of them really will be writers, but ignoring that first piece of advice is inevitable). To them, I say: write what you want to read, what you enjoy reading, because if you’re not enjoying what you’re writing, it will show. But once you’ve decided you simply must write, treat it like a job: learn the tools of your trade (that is, first and foremost, the English language), learn how to tell a story (and how not to) by reading a lot. Follow the rules (Heinlein’s rules of writing, Stanley Schmidt’s “The Ideas that Wouldn’t Die,” and so forth). And then, when you’ve completed the story, treat the concept of getting (and being) published as a business. Present yourself appropriately to editors, readers, and other writers, both in person and online. I could go on at great length, but even my eyes begin to glaze over at this point. Just remember that it’s a fun business to be in, but it is a business, and pissing off potential customers is bad for business.

Hamming it up in the “Eye of Argon” reading at Balticon 2016 with Ian ignoring me in the background. (He was the editor judge!)

Filed under: writing | Tagged: Analog, Asimov's, editing, Fantastic Books, Ian Randal Strock, Ranking the First Ladies, Ranking the Vice Presidents, science fiction, self-publishing, writing advice | 1 Comment »

He’s appeared on CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, the History Channel, NPR, and numerous TV and radio programs. He was President of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America from 1998 to 2001. His web page is

He’s appeared on CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, the History Channel, NPR, and numerous TV and radio programs. He was President of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America from 1998 to 2001. His web page is  Frankly, I think it’s lame to put in discussion questions at the end of a novel which was certainly not intended as a textbook. On the other hand, it has been used as required reading in a few courses over the years, and I’m certainly very happy and grateful for that. I am especially glad, by the way, that I was able to able to write from the perspective of a female hero – Sierra Waters – it was fun writing from the point of view of a gender that’s not you, and I hope I got it mostly right.

Frankly, I think it’s lame to put in discussion questions at the end of a novel which was certainly not intended as a textbook. On the other hand, it has been used as required reading in a few courses over the years, and I’m certainly very happy and grateful for that. I am especially glad, by the way, that I was able to able to write from the perspective of a female hero – Sierra Waters – it was fun writing from the point of view of a gender that’s not you, and I hope I got it mostly right.

He’s the winner of two AnLab Awards from his writings in Analog, and the author of THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS (Random House, 2008), RANKING THE FIRST LADIES (Carrel Books, 2016), and RANKING THE VICE PRESIDENTS (Carrel Books, 2016). His name is unique on the internet, but having such a varied resume means that many of those pages look like they’re talking about different people, so he recently launched

He’s the winner of two AnLab Awards from his writings in Analog, and the author of THE PRESIDENTIAL BOOK OF LISTS (Random House, 2008), RANKING THE FIRST LADIES (Carrel Books, 2016), and RANKING THE VICE PRESIDENTS (Carrel Books, 2016). His name is unique on the internet, but having such a varied resume means that many of those pages look like they’re talking about different people, so he recently launched  He said “I’m not going to make up a limerick for you.” That began our friendship that lasted for the last three years of his life. Two or three months later, Sheila told me one of our authors would be visiting, and I got excited. “I’m going to meet my first author!” I said. And she said “what about Isaac?”

He said “I’m not going to make up a limerick for you.” That began our friendship that lasted for the last three years of his life. Two or three months later, Sheila told me one of our authors would be visiting, and I got excited. “I’m going to meet my first author!” I said. And she said “what about Isaac?” As a small publisher, one of the things I offer authors is a much more personal relationship, so when she asked, I of course said yes. As thanks, she offered me a new collection, and I jumped at the chance. DANCING THROUGH THE FIRE was published on what would have been her 68th birthday last year, and was a Locus Award finalist for Best Collection.

As a small publisher, one of the things I offer authors is a much more personal relationship, so when she asked, I of course said yes. As thanks, she offered me a new collection, and I jumped at the chance. DANCING THROUGH THE FIRE was published on what would have been her 68th birthday last year, and was a Locus Award finalist for Best Collection. I really was looking for the characteristics of the Presidents, trying to figure out if I could predict who the next President would be (and for the last two elections, it turns out that the “average President” I created in the book really does predict the winner).

I really was looking for the characteristics of the Presidents, trying to figure out if I could predict who the next President would be (and for the last two elections, it turns out that the “average President” I created in the book really does predict the winner).

Without going too much into spoilers, it follows the kids of FLESH AND FIRE’s protagonist as they try to make sense of what happened in the first book. I’ve also got a balls to the wall supernatural horror novel called, WE ARE THE ACCUSED, that I’m excited about. It has some of the most intense scenes I’ve ever written, I think.

Without going too much into spoilers, it follows the kids of FLESH AND FIRE’s protagonist as they try to make sense of what happened in the first book. I’ve also got a balls to the wall supernatural horror novel called, WE ARE THE ACCUSED, that I’m excited about. It has some of the most intense scenes I’ve ever written, I think.